It has been argued that the origins of kajrī can be traced back to the age of the Purāṇa-s, the dating of which is highly controversial and can be placed approximately around the IV-V century (Piano 2000: 219).

There is no consensus about the literary antecedents of the genre. It has been claimed that references to kajrī seem to have first appeared in the Bhaviṣya-purāṇa54 (Prasad 1987: 67). Here god Kṛṣṇa describes the rituals that should be observed on the occasion of Haryālī tīj. It is prescribed to perform a pūjā, narrate auspicious stories, and sing songs throughout the night. Having celebrated all the rituals typical of a jāgaraṇ, at sunrise women would bathe in any sacred water body. The observance described in the Bhaviṣya- purāṇa actually seems to refer to Harithālikā tīj also known as celebrated on the third day (tṛtīyā) of the bright fortnight (śukla pakṣa) of the month of Bhādrapada, whereas Kajarī tīja (H. Kajrī tīj) occurs on the third day (tṛtīyā) of the dark fortnight (kṛṣṇa pakṣa) of the month of Bhādoṁ.

According to some scholars, the origins of kajrī are linked to the Śakti pūjā or Gaurī pūjā (Jain 2014: 8). This celebration—a spring festival of harvest—is dedicated to Mahāgaurī, the eighth among Navadurgā-s that is worshipped on the eighth day of Navarātri. On this occasion, women observe a ritual fast that lasts eighteen days. It is a prominent festivity also known as Maṅgalā Gaur and it occurs on Tuesdays (maṅgalvār) in the month of Sāvan. It is believed to be a particularly auspicious occasion for newly married women who perform the pūjā of a Śiva liṅga, praying for the well-being of their spouse and family. It is prescribed for brides to follow this practice for the first five years of marriage. The celebration includes an evening get-together of married women who regale each other with folk tales, traditional games, and typical songs. Young brides are asked to sing so-called ukhāne, improvised compositions in which the wife is not supposed to directly utter the name of her husband, but she has to skilfully intertwine it in rhymed couplets.

The several references to the character of Kṛṣṇa and the numerous episodes of his worldly life provide evidence of a close association of kajrī with vaiṣṇava devotional music. Ultimately, music is a very important component of Kṛṣṇa’s worship, in which a pivotal role is played by the mādhurya bhakti that acquires different features according to the sampradāya or vaiṣṇava religious tradition related to Kṛṣṇa. For instance, in the Vallabhā sampradāya or puṣṭi-mārga (‘the path of grace’), the rāslīlā is an integral part of worship.

The genre of kajrī—as its related intermediate forms—is highly diversified into a wide variety of musical expressions, from folk to the more art-oriented ones.

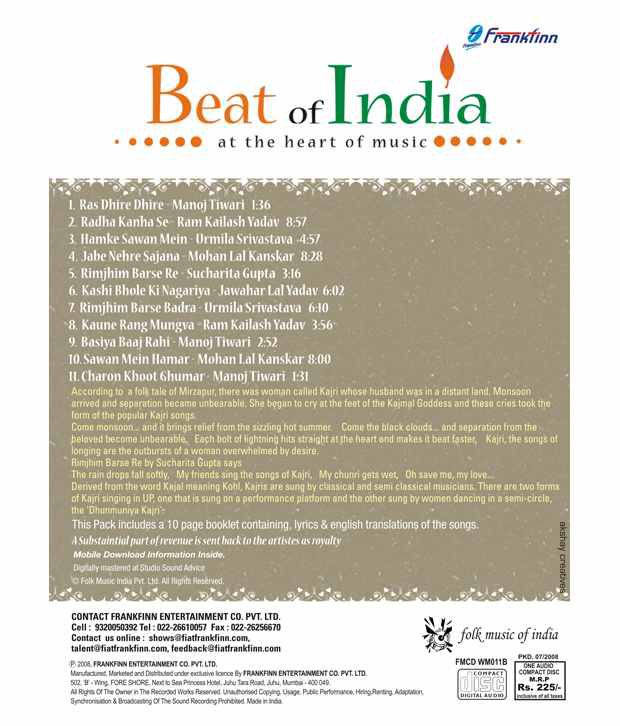

Kajrī is believed to have been born and developed in the area of Mirzapur, in Uttar Pradesh, the location of the famous temple of Vindhyachal. From its original nucleus, the genre spread to other districts of Uttar Pradesh and was cultivated, especially in Varanasi. Mīrzāpurī (alternatively spelt mirjapurī, according to a phonetic trend typical of eastern Hindi forms) and banārsī kajrī are considered ‘proper kajrī’, besides being the most popular and prominent styles of the genre. According to the geographical area, kajrī developed different stylistic features, thematic contents, and musical peculiarities. The genre enjoyed a great diffusion and popularity even in big urban centres, such as Mumbai and Kolkata. In this regard, it is possible to recognise quite different styles in local languages, like the so-called kalkatiyā kajrī and mumbaiyā kajrī distinct from the styles typical of Uttar Pradesh (Prasad 1987: 67).

The above paragraphs are from a rich PhD thesis by Erika Caranti, a German national and scholar. If you have interest in karji, caiti, lavni and other forms of north Indian folk music it is an incredible source of information.

Broadly speaking for the general reader and listener, kajri refers to songs that are sung during the monsoons/rainy season. The most popular examples of the Kajri, a folk song based on the rains, can be found in the Bhojpuri language, but there are similar songs in the sister languages of Awadhi, Maithili, etc. The word ‘Kajri’ comes from ‘kajal’ or kohl, referring to the dark colour of the clouds, which look almost as if they have been smeared with kohl. One also finds a reference to this in the popular phrase ‘kajrare nain’ or dark, kohl-smeared eyes, immortalised in several pieces of music and poetry, as well as in Bollywood songs (think ‘Kajra Re‘ from the soundtrack of Bunty and Babli).